The ISTE Standards for Coaches 4a, “Collaborate with educators to develop authentic, active learning experiences that foster student agency, deepen content mastery and allow students to demonstrate their competency,” speaks to the importance of learning that is both active and authentic for students. In this way, students can better be engaged in learning that empowers them by elevating student agency. When students take ownership of their learning, content mastery and demonstration of that mastery naturally follows suit.

Source: How to Approach Iterating Ed. Tech Professional Learning

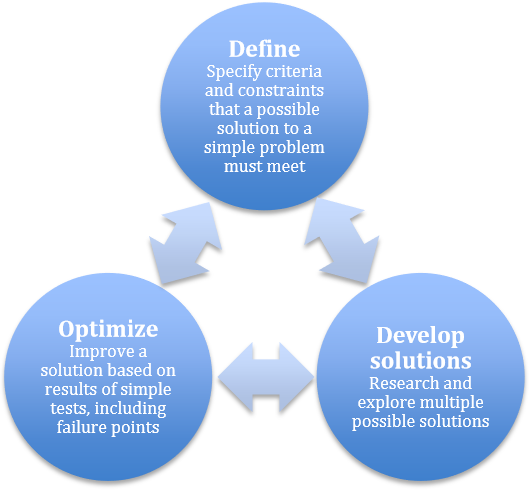

Evidence: “Identifying high-impact teaching and learning approaches can be challenging. Often, for the experienced classroom teacher, the answer is that “I’ll know it when I see it.” While this may be true, such an approach is not systematically applicable. This is where proven research comes into play because the researchers are presumably independent observers applying unbiased, formal methodologies. Still, one of the challenges is utilizing research that is accessible for understanding and application that doesn’t also require extensive training. This is where meta-research done by Robert Marzano and John Hattie becomes relevant. Both researchers/authors provide a summative analysis of multiple studies in a user-friendly format. The result is the ability to look at “effect size” and determine roughly how quantitatively effective a given classroom instructional strategy is on average. By combining this approach along with research-proven approaches such as the 5E model, educators can effectively identify high-impact teaching and learning approaches that they can readily utilize in a classroom setting.”

Explanation: Research-based study and instructional frameworks provide powerful ways for coaches to collaborate with educators and deepen content mastery.

Source: PBL for the Teachers?

Evidence: “A great example of active learning in the classroom is PBL (project/problem based learning). In PBL, students engage directly in the learning by working through a series of involved and individualized steps as part of a group project focused on solving a problem. Adria Steinberg’s “Six A’s of Designing Projects”, as adapted to the The Six “A’s” of PBL Project Design in an article by Andrew Larson, provide a good basic outline of what active learning via PBL looks like. The Six “A’s” identifies the following PBL characteristics: authenticity, academic rigor, applied learning, active exploration, adult relationships, assessment. Students engage with peers in project-based learning that utilizes authentic artifacts and interactive activities at rigorous levels to explore possible solutions and then apply lessons learned—all while interacting with adults as mentors or authentic audience members and being assessed in an authentic manner. This very active learning provides students opportunities to collaborate, be coached, receive relevant feedback, and reflect on their learning both during and immediately after the process. So if all of this active learning happens for student participants in PBL then the obvious question is why not for adult participants? The answer is that it can and should.”

Explanation: Project/Problem Based Learning (PBL) provides one of the most authentic instructional means for collaboration between coaches and teachers. The learning experiences foster student agency and deepen content mastery while empowering students to authentically demonstrate their competency.

Source: Puzzling Over Protocols

Evidence: “In other words, what role can protocols play in adult professional learning taking place in an Ed. Tech environment? Regardless of the adult learning framework being implemented for a given instructional context, protocols can play an important role in several ways.

- Equity of Voice: protocols make sure that everyone is heard by regulating airtime and encouraging reluctant participants to speak.

- Accountability: protocols hold learners accountable for their learning in a positive way by communicating to participants their expected level of engagement and contributions.

- Reducing Social Anxiety: protocols provide transparent expectations of participation in advance of the activity so that nervous participants know exact expectations which reduces anxiety-inducing unknowns.

- Equity of Expertise: protocols level the playing field within a learning environment by elevating new learners, empowering all learners with new knowledge, and limiting the ability of participants to “self-designate” as experts on the subject matter of the training activity.

- Engagement management: protocols can limit participants from dominating a group while also engaging more reticent participants by assigning jobs to participants so as to disperse responsibilities among the learners and lead to a more effective group dynamic.

- Time management: protocols provide a structured means for managing the length of a given activity as well as regulating the allotted discussion time in an equitable manner.

These are just a few examples of the way protocols can function within an adult instructional framework, or any instructional context for that matter. Protocols serve as an efficient and effective means for actively engaging participants in their learning. If you’re looking for a list of possible protocols to explore then I recommend starting with this list from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. In addition to the jigsaw protocol, the list contains 18 common suggestions (with more linked at the bottom of the list). Select one carefully with your instructional content and context in mind, then practice implementing several times to become comfortable before moving on to another. In time, protocols can take care of the “how” of learning in an efficient way so that all involved can focus on investing energy in the aspects of instruction that drive the “why” behind their instruction and learning.”

Explanation: Protocols provide an effective instructional framework that effectively facilitates collaboration among educators in a professional learning setting by focusing interactions on learning. Protocols are powerful in that educators can then turn around and utilize ones that are developmentally appropriate in their own instructional contexts.

Source: Teaching by Design, Part Deux

Evidence: “The “Problem Based Task” category draws on established PBL approaches. I start with the acronym because there are various flavors of PBL, with Problem-Based Learning being one of the more prominent. The original and most well-known is Project-Based Learning. There’s also place-based, passion-based, and phenomena-based among others. All of them are essentially different sides of the same proverbial coin in that the focus is on engaging students with real-world problems and applications of their learning. Dr. Foltos speaks to this in his peer coaching book by citing relevant research on the topic, ”Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (2000) remind educators that real-world problems have to have meaning to their students in their community and need to draw on students’ current knowledge, skills, beliefs, and passions.” He goes onto address some of the critical aspects of Problem-Based activities, “…tasks often consist of two elements: a scenario that will stimulate students’ interest, give them an understandable setting, and define an audience along with an essential question that is designed to define the product the students will create (Meyer et al., 2011).””

Explanation: Dr. Foltos provides some examples of how coaches and teacher can collaborate when thinking about developing authentic, active learning experiences. Drawing on students’ “knowledge, skills, beliefs, and passions” fosters student agency as they prepare to demonstrate any new found competencies.

Source: Teaching by Design, Part Uno

Evidence: ““Tasks are essential in learning that asks students to play an active role in solving real-world problems and develop 21st-century skills. They hook the students, engage their interest in a learning activity, and define how students will demonstrate their learning.” The type of learning tasks that Dr. Foltos is describing in his book on “Peer Coaching” are authentically engaging tasks. For a task to be engaging, it must be developmentally appropriate. Chip Wood’s book, “Yardsticks”, provides developmentally appropriate descriptions that can be extremely useful for appropriate engaging students at certain ages. He speaks to our establish knowledge in this area, “In the first half of the last century, the so-called “giants” in the field of child development—people such as Jean Piaget, Arnold Gesell, Maria Montessori, Erik Erikson, Lev Vygotsky—observed, researched, and recorded most of the developmental patters that form the basis of our knowledge of how children mature.” Meeting students where they are at based on these established “developmental patterns” means we can better engage students.”

Explanation: Collaboration between coach and teacher depends upon collaboration with expert resources such as Dr. Foltos and Chip Wood, their respective resources help align authentic learning experiences through their advocating of real-world problem-solving and developmentally appropriate activities. These foster active learning, student agency, and content mastery.

Evidence: “Being a collaborator means “Working together with colleagues to plan, implement, and evaluate activities,” (Foltos, 2018). This means “Addressing the potential fear-factor of working with an instructional coach”, which can be accomplished by modeling risk taking as mentioned in the facilitator role and providing a safety net within the relationship, “Their efforts to encourage their peers to adopt more innovative teaching and learning strategies are always undergirded by the safety net they built with their collaborating teachers,” (Foltos, 2013). When collaborating, you’re often preparing, planning, teaching and reflecting together with a focus on student learning. The reflecting is where the trust and safety net come in so that coach and teacher can “discuss what worked and what the peer would do differently next time” in a safe manner, (Foltos, 2013).”

Explanation: Collaboration between coach and teacher is multi-faceted and only through preparing, planning, and reflecting together with a focus on student learning can many goals such as developing authentic learning experiences and fostering student agency be developed.

Source: Integrating Social Justice and STEM Pedagogy

Evidence: “Meaningful and engaging learning opportunities with the “why” built into the activities provide students with relevancy and reason for their learning. Starting with what students know is arguably the easiest way to build on background knowledge when attempting a new idea or approach in the classroom. School-based solutions have the added advantage of students being able to help their peers and benefit from their solutions. This could be something as simple as friendship solutions, conflict resolution, and addressing litter. Local community issues allow students to engage with what they know at a broader level. Making a difference in what may seem like their broader world can also build confidence combined with important civic engagement lessons. Issues such as retirement community support, homeless shelter needs, and overall safety provide some examples. Global problems provide an opportunity to raise student awareness to a broader level. Many STEM-based resources allow students to now participate in a broader dialogue. Looking at problems to evaluate and propose solutions for such as world hunger, education, and basic health needs are just some of the possible examples.”

Explanation: PBL is a great vehicle for collaboration among coach and teacher as they prepare collaborative student opportunities via PBL. Authentic learning experiences are especially important and both local community issues as well as global problems can actively engage students in ways that foster agency while deepening content mastery.

Source: Social Justice Pedagogy in a Digital Age

Evidence: “In addition to finding technology that empowers students, providing opportunities for students to address social justice issues within their local context is important. Starting small with simple and accessible lessons then building from there. Lessons can be geared around historical social justice efforts such as the women’s suffrage or the civil rights movement. Providing opportunities for anti-bullying and inclusion lessons can help make the concepts more concrete and accessible for students. Additionally, projects that advocate for accessibility or cleaning up litter at the local park or playground can empower students to make a difference within their relevant world of experience. These examples barely begin to scratch the proverbial surface of what is possible, as the possibilities for making change, no matter how small, in the local community are endless and create a positive ripple effect that grows over time and beyond the community itself.”

Explanation: Social justice provides a powerful vehicle for authentic student learning whether the issues are focused at the school level or on historical contexts. With careful collaboration among educators, students can authentically and actively engage across schools settings in ways that foster student agency in related content areas.

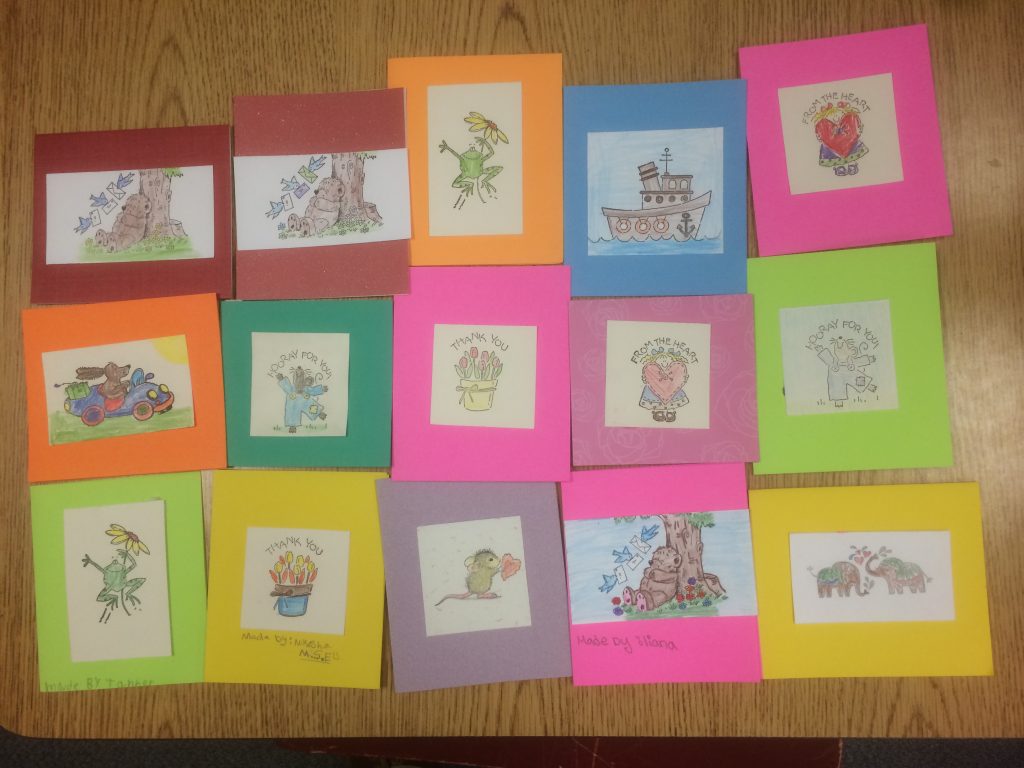

Source: Open Education Resources in Action

Evidence: Starting with a basic example of how to approach, explore, and utilize a specific Open Education Resource is probably the best way to begin to figure out how to approach OERs in general as an educator. AVID Open Access is an OER-style resource that I can speak to based on my experience because I’ve worked directly on the project. While this familiarity may come with a slight inherent bias as a result, it also allows me to more clearly speak to the overall intent of the tool. Here are some general thoughts on how to approach an Open Education Resource based on my work with AVID Open Access. <https://daskalosdouglas.com/stem/open-education-resources-in-action/>

Explanation: Open Education Resources are great examples of collaboration with and among educators as OERs provide a digital virtual library of resources that can be both contributed to and shared. This sharing empowers development of shared learning experiences for students that deepen content mastery and allow students to demonstrate their competency.

Source: Gaming the Educational System

Evidence: “ISTE Educator Standard 5, Designer, provides good guidance for educators in terms of focusing on designing authentic, learner-driven experiences. By focusing on supporting student learning and learner engagement and then matching that with something like game-based learning and gamification, educators can create digital learning environments that explore and apply instructional design principles in truly innovative ways. This type of unique approach can both increase intrinsic motivation and overall student learning at the same time.”

Explanation: Authentic and active learning experiences can be difficult to identify so collaboration can be key and help with learning more about these (rather direct and in person or indirect via a blog). Game-based learning via MakeCode is one such example where students become inherently motivated by the activity which leads toward student agency and an increased likelihood to master content.

Source: Encoding Creative Communication

Evidence: “Again, think computer science for the non-computer science teacher. A classroom teacher interested in incorporating computer science should consider his/her objectives and what s/he is hoping to accomplish with students in the classroom setting. Is the focus on teaching basic programming itself? Problem solving? Content integration? Physical computing? Some combination thereof or something else all together? Additionally, gauging individual comfort level and available resources is important. Code.org empowers the average teacher without any programming background, knowledge, or support to sign up students and get them started together on mostly self-paced programming lessons as well as detailed offline computing lesson plans. The more comfortable or advanced the teacher’s ability then the more robust the example they might try such as programming stories in Scratch from scratch, designing video games in Arcade, writing programs for micro:bit microcontrollers in MakeCode, or even exploring entirely new avenues like programming 3-dimensional shapes in Minecraft for virtual interaction or Tinkercad for physical printing via their respective coding environments. The hardest part is starting but the journey of a thousand programming steps begins with that very first coded “Hello World” program. From there, the possibilities are infinite and students will no doubt exceed any expectations.”

Explanation: Programming in general creates authentic opportunities for activity learning and collaboration around learning experiences. The power of being a programmer fosters student agency, content mastery, and provides a product for demonstrating student learning.

Source: Computational Thinking Across the Content Areas

Evidence: “Now comes the more challenging task of applying computational thinking to those content areas that we don’t normally think of as applicable. By focusing on the four pillars of computational thinking, we can start to think about what this might look like. At its core is probably pattern identification. So we need to start thinking about everything in terms of patterns. Computer science is patterns of binary logic and mathematics is patterns of numbers. Beyond these two, art is patterns of lines, reading is patterns of letters, writing is patterns of words, science is patterns of ideas, engineering is patterns of science applied to or with technology, history is patterns of events, music is patterns of notes, etc. This list is probably an oversimplification but you get the idea that we can look at everything as being composed of patterns, and if we can do this then we can use a problem solving approach like computational thinking that relies on patterns to solve problems across all of these content areas.”

Explanation: Computational thinking provides rigorous learning experiences for students that allow them to deepen content mastery across content areas. Computational thinking is a nascent pedagogical approach where collaboration can be the key for educators to unlock the possibilities.

Source: Design Process Quiddity

Evidence: “ISTE Standard 4, Innovative Designer, describes a level of foundational design skills that students should possess. While not a design process itself nor referencing a specific design process, the ISTE standard describes the need for students to be able to generate ideas and utilize the design process to solve open-ended problems that require iterative solutions. This generic and process-agnostic approach, makes the Innovative Designer standard an ideal educational foundation for this work.”

Explanation: Innovative design and design processes are inherently collaborative and as opportunities for students provide authentic learning opportunities that foster student agency as they seek to demonstrate solutions to problems discovered as they deepen content mastery.

Source: Setting the Standard for Student Empowerment

Evidence: “Fortunately, two great resources provide examples that can help address this question. The “ISTE Standards for Students” ebook provides several helpful vignettes. One of which is sample scenario 2 for ages 8-11 and describes the role that ISTE standards can play in “Solving Real-World Community Problems”. The US Department of Education also provides a report entitled “Innovation Spotlights: Nine Dimensions for Supporting Powerful STEM Learning with Technology”. The seventh dimension shared provides both a description and a case study for “Project-based Interdisciplinary Learning”. The examples show how technology potentially supports, intersects, and overlaps with other disciplines, as well as how technology empowers student learners.”

Explanation: Identifying resources where educators collaborated to share insights amplifies teachers’ overall collaborative ability as they leverage potential frameworks for deepening content mastery and allowing student to demonstrate competency.

Source: The Three Dimensions of the NGSS According to Science Cat

Evidence: “The NGSS is composed of the DCI’s, CCC’s, and Science and Engineering Practices… great, more acronyms, right? A lot of really smart people are doing some incredibly deep and serious analysis of this stuff. So much so, that I am nowhere near comfortable doing a full break down yet. In fact, there are so many books written on this topic already that even trying to do so in a blog post would be either a disservice, dishonest, or both. I need to read a few more books before I even pretend to have an informed professional opinion. So, I did the next best thing. By popular request from previous readers, I asked my cat. The following is a breakdown of the three dimensions of the NGSS from a cat’s perspective. It’s probably not going to add any insight to the conversation, but (and this is a big but), I’m willing to wager that you have yet to be instructed on the NGSS by a cat so your chances of remembering details that are helpful for the average classroom teacher are slightly higher. Plus, you are (as a reader), inevitably smarter and more discerning than my cat.”

Explanation: Teacher blogs provide great opportunities for collaboration and can be serious or whimsical. By learning from other teachers’ examples, educators can glean authentic ideas for fostering student agency and deepening content mastery via established national standards such as the Next Generation Science Standards.

4a Authentic, active learning experiences