Introduction

How do we begin to evaluate professional learning? What are the most desirable aspects? When, how, and why do we utilize technology? What makes certain pedagogical approaches “high-impact” from both the teaching side of things as well as the learning end? How do we ensure that “student learning” remains first and foremost? In the end, it’s all about the students, right? These are all questions that run through my mind as I read ISTE’s Instructional Coaching Standard 5c. There is a lot going on in the language of this standard. If we assume that the schoolwide vision is discernable and agreed upon at the classroom level, which is a very big “if” and assumption, then we’re still left with a lot of questions to answer beyond that foundational aspect. There are no shortage of complex problems such as this in education, and complex problems are worth exploring. Perhaps a close look at the standard followed by a reframing of the standard’s language into a question will prove helpful in beginning to break down this complex myriad of ideas into individually addressable parts.

Standard

- ISTE Standard 5c Evaluate the impact of professional learning and continually make improvements in order to meet the schoolwide vision for using technology for high-impact teaching and learning.

Question

- How does one iteratively design a professional learning experience on using technology for high-impact teaching and learning?

Beginning with the End in Mind

Understanding by Design focuses us as educators on working backward in our design of educational approaches and experiences by beginning with the end in mind. In the classroom, this applies to lesson and unit planning. With regard to professional learning, student learning is the end goal. Answering the question up above means starting with identifying as best we can what is meant by “high-impact teaching and learning.” Appropriately, Understanding By Design also advocates for the use of the Essential Question in terms of guiding work. So let’s work backward by design to address the essential question proposed above.

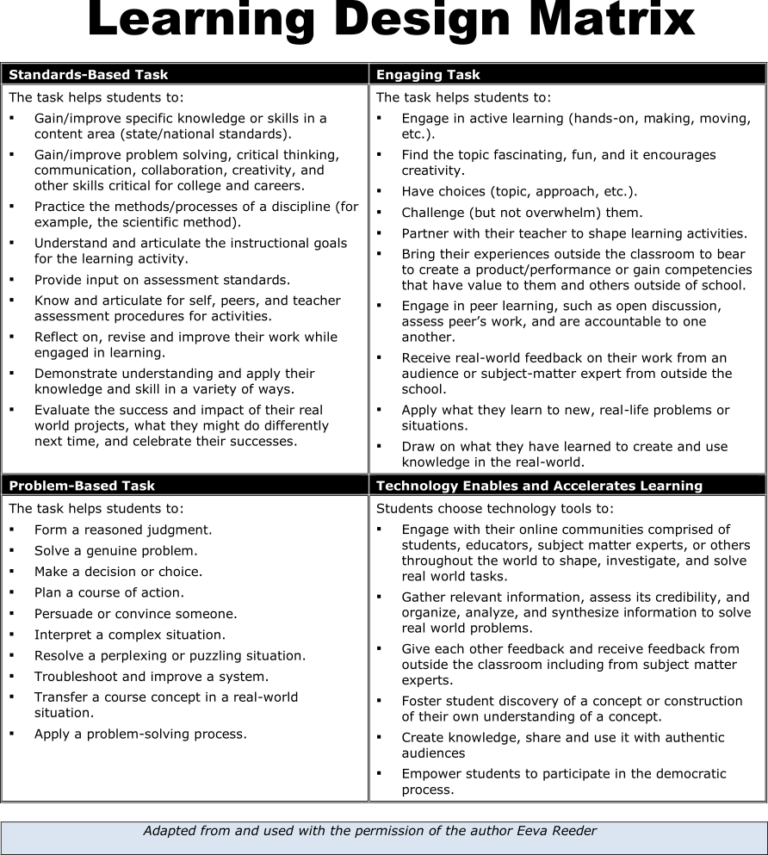

Identifying High-Impact Teaching and Learning Approaches

Identifying high-impact teaching and learning approaches can be challenging. Often, for the experienced classroom teacher, the answer is that “I’ll know it when I see it.” While this may be true, such an approach is not systematically applicable. This is where proven research comes into play because the researchers are presumably independent observers applying unbiased, formal methodologies. Still, one of the challenges is utilizing research that is accessible for understanding and application that doesn’t also require extensive training. This is where meta-research done by Robert Marzano and John Hattie becomes relevant. Both researchers/authors provide a summative analysis of multiple studies in a user-friendly format. The result is the ability to look at “effect size” and determine roughly how quantitatively effective a given classroom instructional strategy is on average. By combining this approach along with research-proven approaches such as the 5E model, educators can effectively identify high-impact teaching and learning approaches that they can readily utilize in a classroom setting.

Utilizing Technology to Support High Impact Teaching and Learning

Working backward from high-impact teaching and learning approaches with respect to our essential question, we can analyze where technology comes into play with respect to a potential schoolwide instructional vision and quality professional learning. A book that provides a nice bridge between meta-research and technology implementation is The Distance Learning Playbook written by Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Hattie. In speaking to the challenge of identifying effective instructional strategies as a lead into their book on the application of technology, the authors state, “But the fact of the matter is that some things work best. Thus, it’s useful to know what works best to accelerate student’s learning.” “What works best” can then be applied to utilizing technology schoolwide. Along these lines, Learning First, Technology Second by Liz Kolb provides good insights and a framework for analyzing technology integration. She refers to this as her Triple E model and looking through the lens of Engagement, Enhancement, and Extension allows for an analysis of technology integration and application as well as a good starting point for thinking about potential connections to professional learning that addresses technology.

Iterative Design of High Impact Professional Learning

With respect to the question posed above, identifying high-impact teaching and learning via research and analyzing technology with both research and frameworks allows for professional learning that addresses all of this, with respect to the schoolwide vision, to be iteratively designed. A combination of asking teachers, staying grounded in research, and formatively assessing the professional learning experiences are key. Directly asking teachers about their professional learning needs is important and a Gates Foundation report entitled Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development does exactly that. Teachers want instructional coaches and staff developers that “know what it’s like to be in their shoes”, they want well-structured collaboration opportunities, and they want choice among other things. Research backs a lot of this up as well, although, with caveats. While workshops and professional trainings are supported to a degree in research, ongoing and targeted professional learning are key which really supports instructional coaching models. Instructional coaching can be informal, formal and regular 1:1 meetings, as needed, at the instructional team or Professional Learning Community level, and/or consist of before/after school trainings as well as workshops. Per Peer Coaching : Unlocking the Power of Collaboration, “If schools want wide-scale adoption of innovative practices, teachers need a mentor or coach at each step in the process of adaptation and adoption.” The key is that the professional learning supported by the instructional coach consists of consistent and targeted learning.

Ending with the End in Mind

With all of this in mind we’ve arrived at the end with the end and essential question in mind: How does one iteratively design a professional learning experience on using technology for high-impact teaching and learning? By building on everything described so far, effective professional learning can be designed and provided. In order to iterate, professional learning results need to be actively researched and monitored. By pre-assessing participants in advance, formatively assessing professional learning while it’s taking place, and summatively assessing via follow-up surveys, professional learning experiences can be monitored and improved upon. Tracking and implementing adjustments made during facilitation are important and when combined with valuable participant feedback, powerful iterative improvements can be made which result in ever increasing effectiveness of the targeted professional learning. There’s a lot more to approaching active research with respect to improving professional learning but intentional assessment is the place to start. For learning more around identifying how best to procure the desired data for ongoing program evaluation, seek out research guides and resources such as “Small Scale Evaluation: Principles and Practice”, and you’ll soon be unlocking elements of your own professional learning along the way to helping and supporting others.

References

- International Society for Technology in Education. (2019). ISTE Standards For Coaches. ISTE. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/standards/for-coaches

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2014, December). Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved from http://k12education.gatesfoundation.org/download/?Num=2336&filename=Gates-PDMarketResearch-Dec5.pdf

- Les Foltos. (2013). Peer Coaching : Unlocking the Power of Collaboration.

- Marzano, R., Pickering, D., Pollock, J. (January, 2001). Classroom Instruction that Works. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., Malenoski, K. (2007). Using Technology with Classroom Instruction that Works. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development & Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning.

- Bybee, R. (2015). The BSCS 5E Instructional Model. National Science Teachers Association.

- Fisher, D., Frey, N., Hattie, J. (2020). The Distance Learning Playbook. Corwin.

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers. Routledge.

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, Jay. (2005). Understanding by Design (Expanded 2nd ed., Gale virtual reference library). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Corwin.Kolb, L. (2017). Learning First, Technology Second. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

- Terada, T. (2021, February). New Research Makes a Powerful Case for PBL. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/new-research-makes-powerful-case-pbl?utm_content=linkpos5&utm_campaign=weekly-2021-02-24&utm_source=edu-legacy&utm_medium=email

- MIT Kindergarten Learning Book

- Scott, M. (2019, July). A Unity of Purpose and Action. Communicator (Vol 42, Issue 11). Retrieved from https://michaelfullan.ca/articles/

- Robson, C. (2000). Small Scale Evaluation: Principles and Practice. SAGE Publications Ltd.