What do the Standards Say?

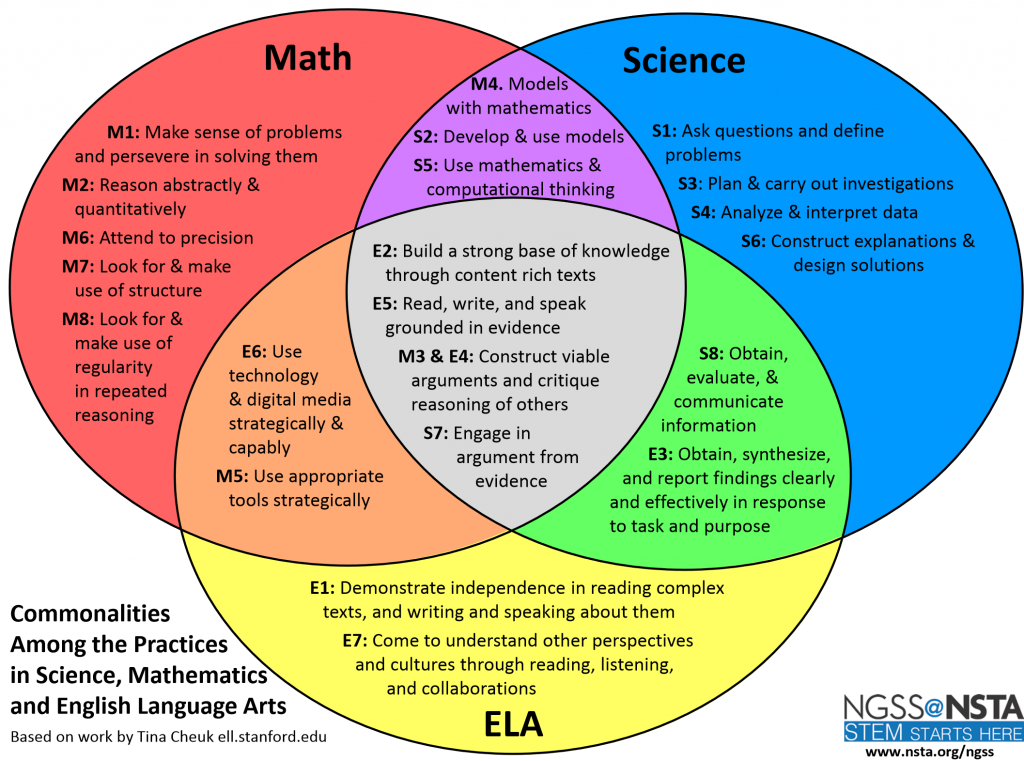

A standards-based approach drives much of what we do in education. At the end of the day, we should also teach content because it’s needed and the right thing to do in addition to being aligned with standards. When it comes to accurately researching factual information and recognizing misinformation, “all of the above” applies. The English Language Arts Common Core State Standards provide strong support through the Capacities of the literate individual: They demonstrate independence; They build strong content knowledge; They comprehend as well as critique; They value evidence; They use technology and digital media strategically and capably. We also find support in the Practices of the Next Generation Science Standards where the following is stated: Analyzing and Interpreting Data; Constructing explanations; Engaging in argument from evidence; Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information. Determining accuracy of information is critical to these standards. Even the Common Core State Standards for Mathematical Practice speak to this need as students are tasked with being able to “Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.” In terms of the modern era, there is a deluge of information published online every day so it makes sense that we’d look to the ISTE technology standards as a starting point for teaching these skills in support of all standards. It just so happens that ISTE Standard 3 is well-suited to this task.

ISTE Standard 3

Knowledge Constructor: Students critically curate a variety of resources using digital tools to construct knowledge, produce creative artifacts and make meaningful learning experiences for themselves and others. Students:

- Plan and employ effective research strategies to locate information and other resources for their intellectual or creative pursuits.

- Evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources.

- Curate information from digital resources using a variety of tools and methods to create collections of artifacts that demonstrate meaningful connections or conclusions.

- Build knowledge by actively exploring real-world issues and problems, developing ideas and theories and pursuing answers and solutions.

Being able to “critically curate a variety of resources” requires a variety of research-focused abilities: knowing how to conduct online searches, being able to determine the authenticity of websites and online information sources, analyzing the accuracy of the information itself as presented, understanding how to conduct the verification process, and being able to appropriately cite resources. ISTE Standard 3 provides guidelines for teaching these concepts as well as communicating the need for students to be technically capable enough to organize the information via a curation process and worldly enough to engage in content with a real-world context.

Essential Question

How do we teach students to critically evluate resources in such a way that they are able to effectively discern misinformation and other “fake news” from legitimate sources?

Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News

“Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” is the cleverly titled presentation that I recently attended at the December, 2019 AVID National Conference. The presenters, Laurie Kirkland and Pat Regnart, walked attendees through a plethora of information and resources on the topic. While fully engaged, I felt as though I barely scratched the surface in terms of content. With the topic of this article fully established and that in mind, the remainder of the content will be exploring ISTE Standard 3 through the lens of the presentation entitled “Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” and its primary focus on “Evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources.”

Where do I even begin?

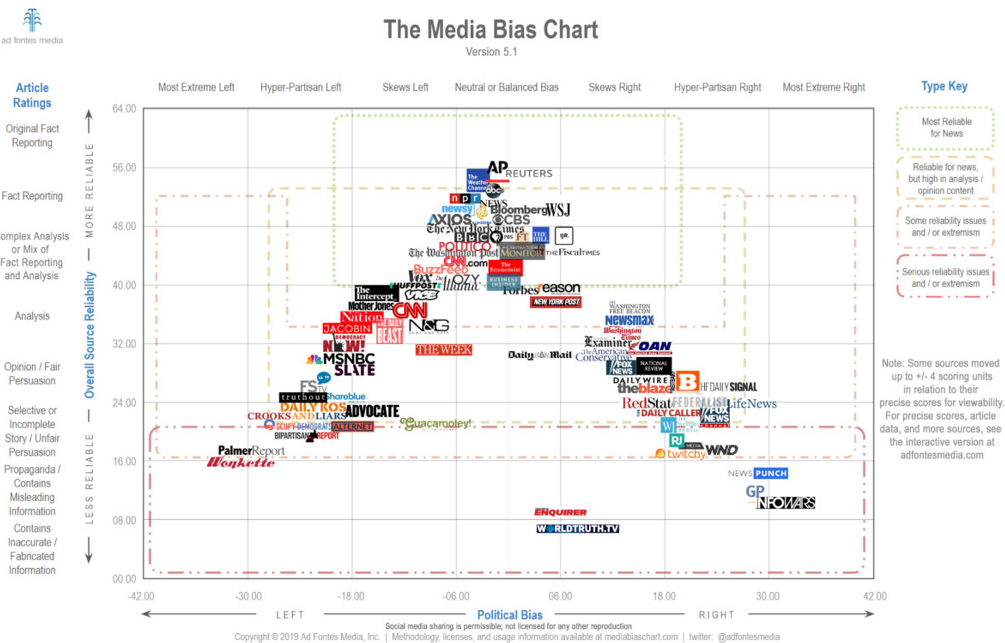

This article’s title graphic shows the inherent bias that even professional news media possess, but awareness of bias is just the start because knowing how to spot “fake news” is a skill that needs to be developed. According to a recent Stanford study cited by NPR, a relatively high percentage of surveyed students do not know how to spot falsification of information, “… at times as much as 80 or 90 percent…” A resource referenced by the “Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” presentation shares a great tool toward this end. Entitled “Evaluating a News Article”, the infographic walks the reader through asking several questions including the following examples: Does the headline match the content? Are there spelling or grammatical errors? Who is the Author? Are there references, links or citations? What is the website? Teaching these kinds of critical thinking and questioning skills is essential to developing students that turn into well-informed global citizens.

Evaluating Resources

Understanding primary purpose of media and the various types of misinformation (also known as “fake news”), this is an area where the “Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” presentation was especially helpful. The presenters outlined the following categories for media purpose: entertain, sell, persuade, provoke, document, and inform. Understanding the purpose behind a media piece can be very helpful in terms of navigating the accuracy of information provided. Context is everything, and most likely the author has his or her own self-serving reasons for producing something. Taking things a step further and understanding the types of misinformation makes it easier to identify “fake news” when a reader encounters. Presented examples included satire, false context, imposter content, manipulated content, and fabricated content. Satire, for example, is not bad but important to recognize for understanding while understanding the other types helps the educated reader remain vigilant. Although limited, when in doubt then a reader can utilize a website such as Snopes or FactCheck.org to verify specific statements. Ultimately, the reader needs to be able to be an effective judge of content in the moment or they won’t even necessarily think about the need to verify information via a third source (as all information should given even the smallest doubt and especially before referencing elsewhere).

Digging Deeper

Effective classification of websites enables the ability to curate information that those websites contain, and knowing what tools exist to facilitate this process is an important facet of evaluating resources in the process. Most websites can be classified by their intended purpose and most fall under the aforementioned categories ranging from entertainment to provocation to information. Digging deeper is made easier by knowing both how and where to look. The “Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” presenters shared several search tools that can help with information verification and include the “info:” search tool as well as the “link:” search tool (utilized by placing either term in front of your search). These allow targeted searches where as the “Whois” search tool provides detail background information on a given web address and the “Wayback Machine” allows the user to search old archived versions of websites and articles. This is also a good lesson for students that shows them once something is online then it can stay online indefinitely—even if it is supposedly deleted.

Practice and Application

Scaffolding student practice of effective research strategies, evaluating resources, and curating information is necessary for students to internalize and build effective knowledge around identifying, understanding, and navigating a world filled with fake news. By teaching students how to recognize media and author bias, look for “fake news” clues in an article, recognize categories of media and misinformation, and then providing them with the appropriate tools and time to practice, students can become effective consumers and curators of information from a very young age. Some possible places to start include providing access to a variety of websites designed for this exact purpose: the Pacific Northwest Octopus, OvaPrima Foundation, Dihydrogen Monoxide Research Division. These also provide good places to practice site-specific searches by entering the unique web address immediately followed by a colon, a space, and then the search criteria. Overall, we as educators need to provide the information, tools, time, and space for students to do this.

Foreshadowing the Challenge Ahead

One final thing worth noting here is a random conversation at ISTE that predates all of this. I had an impromptu opportunity to converse with the soon-to-be presenters of “Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News” and Alan November. One thing that Alan was adamant about was that we do not give young students enough credit for the level of search sophistication which they are capable. The conversation took a myriad of twists and turns but his insistence on providing opportunities for students to learn, search, and navigate online resources from second grade on stuck with me because of both his passion and examples of having observed these young students successfully doing so firsthand. So I guess the question is, “What’s stopping the rest of us?”

*It is worth noting that, during the writing of this article, the following misinformation around the Coronavirus went viral in a school community and required a response from the local school district: https://ktar.com/story/2947583/mesa-school-district-debunks-hoax-about-coronavirus-infecting-students/.

References

- Kirkland, L. & Regnart, P. (2019, December). Digital Literacy in the Age of Fake News: Misinformation, Bias, and Checking for Accuracy. AVID National Conference. Talk presented at 2019 AVID National Conference, Dallas, TX.

- Ad fontes media (2019). Media Bias Chart 5.1 – Static Version. Retrieved from https://www.adfontesmedia.com/static-mbc/?v=402f03a963ba

- Domonoske, C. (11/23/2016). Students Have ‘Dismaying’ Inability To Tell Fake News From Real, Study Finds. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/11/23/503129818/study-finds-students-have-dismaying-inability-to-tell-fake-news-from-real

- Kirschenbaum, M. (02/01/2017). Identifying Fake News: An Infographic and Educator Resources. Retrieved from https://www.easybib.com/guides/evaluating-fake-news-resources/

- November Learning (2019). About November Learning. Retrieved from https://novemberlearning.com/educational-services/

- Common Core State Standards Initiative. Common Core State Standards. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/

- The Next Generation Science Standards for States by States. Next Generation Science Standards. Retrieved from https://www.nextgenscience.org/

- International Society for Technology in Education (2016). ISTE Standards For Students. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/standards/for-students