Live and In-person to Virtual, Remote, & Online Learning

Every year as part of my job as a learning designer, I help to design, host, and train teachers that will be running professional development training over the coming year. We do this training in person over the course of a long weekend. So what happens when that training suddenly has to pivot to being done online? How do we adapt? What does that even begin to look like? So many questions! And, not a lot of answers. In some ways, I feel fortunate because I’m trying to figure out how to host online training for adults as opposed to many of my k-12 teacher friends that are currently trying to figure out how to approach a similar shift with kids. All the same, I think there are some similarities, and right now is a good time to share thoughts around what’s sure to be a common challenge faced by many educators across the country and even around the world. In some ways, this is much bigger than any of us as individuals or as educators and is a question of citizenship because the root cause is a global pandemic. Since we’re taking this online, it’s a good opportunity to review digital citizenship as outlined by the International Society for Technology Education (ISTE) Standards.

International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Standard 2

ISTE Standard 2, Digital Citizen, students recognize the rights, responsibilities and opportunities of living, learning and working in an interconnected digital world, and they act and model in ways that are safe, legal and ethical. Students will:

- Cultivate and manage their digital identity and reputation and are aware of the permanence of their actions in the digital world.

- Engage in positive, safe, legal and ethical behavior when using technology, including social interactions online or when using networked devices.

- Demonstrate an understanding of and respect for the rights and obligations of using and sharing intellectual property.

- Manage their personal data to maintain digital privacy and security and are aware of data-collection technology used to track their navigation online.

As we look at being good citizens overall during a challenging time, thinking about what good online citizenship means is a good review and preparation for better overall interactions and guiding of learning online. Acting in model ways that are safe, legal, and ethical are important ideas to keep in mind. As educators, we should model the type of choices and behaviors that we want to see from our students. Online actions are much more permanent because there’s a digital record so being cognizant of this is important. Assuming positive intent is especially important because tone and body language are often hard to communicate online. Additionally, a genuine understanding and respect for intellectual property is important online as well as a general area for improvement in education. Finally, managing personal data as an educator means not only monitoring your own personal data but protecting that of those whom you work with and teach as well. All of these things are natural extensions of good citizenship during the best of times let alone during challenging times, and extending these critical ideals to an online learning environment will make for a much better and overall more productive experience for everyone.

Essential Question

How do teachers shift from in-person professional development to virtual online learning for their own edification and what are the andragogical versus pedagogical implications?

Shifting from Face-to-Face to Online Face Time

Synchronous Video Chat Programs with Chat Rooms: Transitioning from face-to-face in person to face-to-face online is not as straightforward as one might imagine. It is difficult to engage a large group via video chat. Some programs support up to 9-10 in a group well but once you grow beyond the “brady bunch” frame then it’s extremely difficult to have small interactions that normally occur in an in-person large group setting. So this medium cannot just be approached as a substitute for in-person but as its own unique thing and as a different way to engage a group of people. For example, one difference that can be an enhancement is the back-channel chat that allows more voices to be heard without interrupting the presenters and also allow for more interaction. This combined with breakout rooms for smaller chats that can instantaneously become small group discussions or work groups which can then regroup with the large group. Some examples of common video chat programs are Skype, Google Chat, Zoom, WebEx, Teams, Big Blue Button, and Google Meet, but there are definitely many more options out there.

Asynchronous Video Chat Programs: This is where online gets more interesting, in my opinion, and it can truly augment in-person interactions. The ability to record short videos that can then be shared with a group, interacted with, commented on, and viewed or saved for later enhances in-person as well as remote interaction adds quite a bit to the learning experience. There are many options and programs that can be used for this approach, including many of the common video chat programs. The one that is most common and launched this kind of interaction to the mainstream is called Flipgrid. Approaching online interaction with unique tools and approaches helps to make the time more engaging and compensate for some of the aspects lost from being all together. Whether live or virtual, at the end of the day, it all comes back to relationships and a sense of community among participants and the instructors.

Online Professional Development Beyond the Video

Interactive note-taking applications: This is one type of tool that allows for a fair amount of asynchronous interactivity online but is not a huge shift for users. These are not too different from current computer word processing applications except that they add an interactive collaboration component. Google Docs, Word 365, and OneNote are all great examples of spaces where people can share their notes together and add information while watching the same presentation, in a meeting, or working asynchronously on a particular problem.

Interactive annotation applications: A slight variation on interactive note-taking is digital annotation web applications, which are becoming common. These allow for a commonly selected text to be shared and then both highlighted and commented on in such a way that all participants can interact with the information and grow the interactive annotation into a more global conversation. Perusall and Edpuzzle are great examples. Edpuzzle even allows the usage of digital media with questions inserted by an instructor for a slight variation on the task. This is also an excellent way to practice digital citizenship in terms of both honoring and emphasizing intellectual property.

Interactive brainstorming: This is another take on web collaboration and allows everything from a virtual whiteboard to an online mind map to virtual sticky notes. Virtual whiteboards, like Miro, allow for people to virtually interact in a Whiteboard space. The disadvantage is the lack of kinesthetic movement in the space and interactivity but the advantage is that the work is instantaneously saved and people can work on the project asynchronously from any location. If mind mapping is the focus then Coggle is a great resource for quick and efficient mind maps outlining ideas, workflows, and similar tasks.

Additionally, padlet allows for interactive usage of sticky notes and is a great way to conduct online group interactions, thinking, brainstorms, and reflections. Again, the information is automatically saved for later review and accessible to any group members at a later time for reference.

Less Obvious Online Interactions

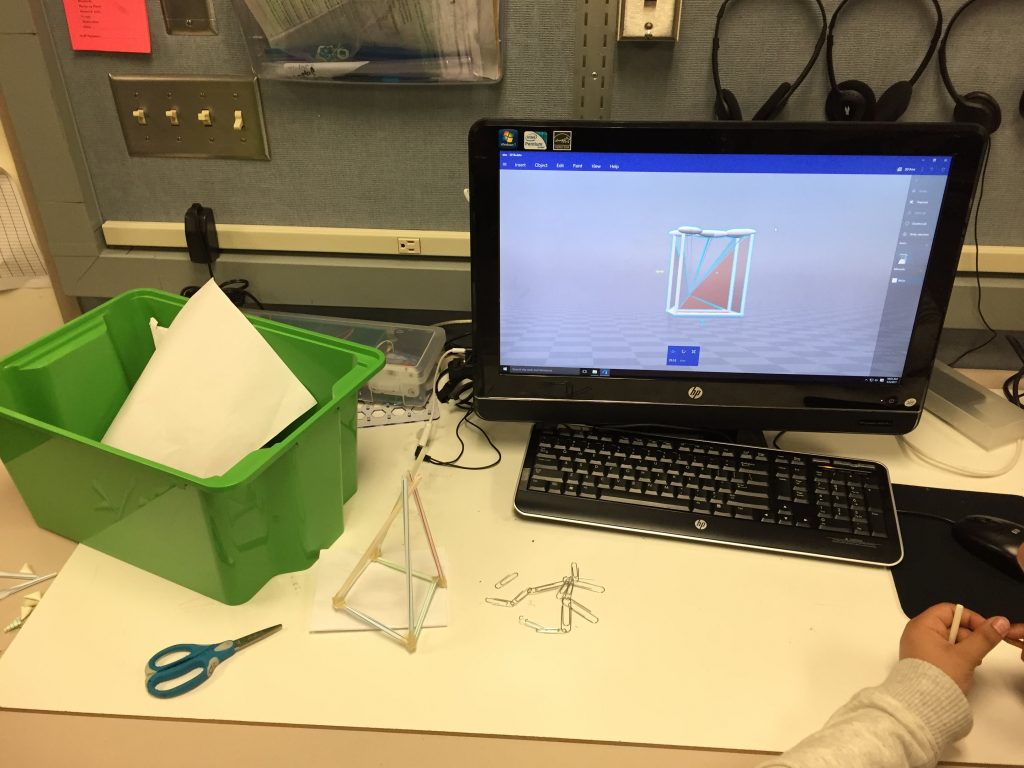

While somewhat less obvious, online simulations and interactive coding opportunities provide new and unique ways for participants to experience a virtual version of hands-on learning. Freely available PhET simulations from the University of Colorado are a great option for both math and science simulations that can be done via a computer, tablet, or phone. Block-based coding software makes computer programming much more accessible and can be both quickly learned and shared via platforms such as Code.org, Scratch, MakeCode, and Polyup to name just a few.

Completely Synchronous to Asynchronous and Beyond

When pivoting from in-person synchronous to online synchronous and asynchronous, I think the main lesson to learn is that there are very few direct substitutes or replacements. Most interactive online learning tools have their own advantages and disadvantages when compared with in-person learning. Most importantly, there are many ways in which these online tools can also be used to augment and improve in-person professional development. This is probably the best of both worlds where both tools can be used to supplement, complement, enhance, and amplify learning together. In this way, tools such as Google Office and Microsoft Office 365 can be used both in person and online. These traditional office tools now have several options for online collaboration and can make working together digitally more seamless when done both in-person and virtually as well as synchronous activities combined with asynchronous activities.

How then does the average classroom teacher apply this? This is a question that’s been in the back of my mind as I prepare to adapt adult professional development and many of my peers prepare for their students to learn remotely. In some ways, this means looking at where the andragogical aspects end and the pedagogical implications begin. In other ways, it means simply jumping in, trying whatever you can, doing your very best, and giving yourself permission to struggle, fail, and try again with different approaches. Normally, I’d recommended starting small and just trying an activity here or there but recent events mean many educators are going from all in-person learning to completely online learning environments virtually overnight. This is a challenging transition in the best of circumstances, and so I hope my colleagues will give themselves and their students grace while they try to learn in a brave new virtual world that’s familiar only to some and foreign to most. I know it can be done, though, I believe in my fellow educators, and I hope that somehow I can help support them as we all work through these unique circumstances together.

References

- MIT. (2020). Scratch. Retrieved from https://scratch.mit.edu/

- Code.org. (2020). Hour of Code Full course catalog. Retrieved from https://studio.code.org/courses

- Microsoft. (2020). MakeCode. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/makecode

- Polyup. (2020). Poly Challenge. Retrieved from https://www.polyup.com/

- International Society for Technology in Education. (2016). ISTE Standards For Students. ISTE. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/standards/for-students